M m 1 Processor Sharing Response Time Not Continuous

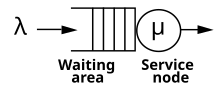

In queueing theory, a discipline within the mathematical theory of probability, an M/M/1 queue represents the queue length in a system having a single server, where arrivals are determined by a Poisson process and job service times have an exponential distribution. The model name is written in Kendall's notation. The model is the most elementary of queueing models[1] and an attractive object of study as closed-form expressions can be obtained for many metrics of interest in this model. An extension of this model with more than one server is the M/M/c queue.

Model definition [edit]

An M/M/1 queue is a stochastic process whose state space is the set {0,1,2,3,...} where the value corresponds to the number of customers in the system, including any currently in service.

- Arrivals occur at rate λ according to a Poisson process and move the process from state i to i + 1.

- Service times have an exponential distribution with rate parameter μ in the M/M/1 queue, where 1/μ is the mean service time.

- All arrival times and services times are (usually) assumed to be independent of one another.[2]

- A single server serves customers one at a time from the front of the queue, according to a first-come, first-served discipline. When the service is complete the customer leaves the queue and the number of customers in the system reduces by one.

- The buffer is of infinite size, so there is no limit on the number of customers it can contain.

The model can be described as a continuous time Markov chain with transition rate matrix

on the state space {0,1,2,3,...}. This is the same continuous time Markov chain as in a birth–death process. The state space diagram for this chain is as below.

Transient solution [edit]

We can write a probability mass function dependent on t to describe the probability that the M/M/1 queue is in a particular state at a given time. We assume that the queue is initially in state i and write p k (t) for the probability of being in state k at time t. Then[2] [3]

where is the initial number of customers in the station at time , , and is the modified Bessel function of the first kind. Moments for the transient solution can be expressed as the sum of two monotone functions.[4]

Stationary analysis [edit]

The model is considered stable only if λ < μ. If, on average, arrivals happen faster than service completions the queue will grow indefinitely long and the system will not have a stationary distribution. The stationary distribution is the limiting distribution for large values of t.

Various performance measures can be computed explicitly for the M/M/1 queue. We write ρ = λ/μ for the utilization of the buffer and require ρ < 1 for the queue to be stable. ρ represents the average proportion of time which the server is occupied.

Average number of customers in the system [edit]

The probability that the stationary process is in state i (contains i customers, including those in service) is[5] : 172–173

We see that the number of customers in the system is geometrically distributed with parameter 1 −ρ. Thus the average number of customers in the system is ρ/(1 −ρ) and the variance of number of customers in the system is ρ/(1 −ρ)2. This result holds for any work conserving service regime, such as processor sharing.[6]

Busy period of server [edit]

The busy period is the time period measured between the instant a customer arrives to an empty system until the instant a customer departs leaving behind an empty system. The busy period has probability density function[7] [8] [9] [10]

where I 1 is a modified Bessel function of the first kind,[11] obtained by using Laplace transforms and inverting the solution.[12]

The Laplace transform of the M/M/1 busy period is given by[13] [14] [15] : 215

which gives the moments of the busy period, in particular the mean is 1/(μ −λ) and variance is given by

Response time [edit]

The average response time or sojourn time (total time a customer spends in the system) does not depend on scheduling discipline and can be computed using Little's law as 1/(μ −λ). The average time spent waiting is 1/(μ −λ) − 1/μ =ρ/(μ −λ). The distribution of response times experienced does depend on scheduling discipline.

First-come, first-served discipline [edit]

For customers who arrive and find the queue as a stationary process, the response time they experience (the sum of both waiting time and service time) has transform (μ −λ)/(s +μ −λ)[16] and therefore probability density function[17]

Processor sharing discipline [edit]

In an M/M/1-PS queue there is no waiting line and all jobs receive an equal proportion of the service capacity.[18] Suppose the single server serves at rate 16 and there are 4 jobs in the system, each job will experience service at rate 4. The rate at which jobs receive service changes each time a job arrives at or departs from the system.[18]

For customers who arrive to find the queue as a stationary process, the Laplace transform of the distribution of response times experienced by customers was published in 1970,[18] for which an integral representation is known.[19] The waiting time distribution (response time less service time) for a customer requiring x amount of service has transform[5] : 356

where r is the smaller root of the equation

The mean response time for a job arriving and requiring amount x of service can therefore be computed as x μ/(μ −λ). An alternative approach computes the same results using a spectral expansion method.[6]

Diffusion approximation [edit]

When the utilization ρ is close to 1 the process can be approximated by a reflected Brownian motion with drift parameter λ –μ and variance parameter λ +μ. This heavy traffic limit was first introduced by John Kingman.[20]

References [edit]

- ^ Sturgul, John R. (2000). Mine design: examples using simulation. SME. p. vi. ISBN0-87335-181-9.

- ^ a b Kleinrock, Leonard (1975). Queueing Systems Volume 1: Theory. p. 77. ISBN0471491101.

- ^ Robertazzi, Thomas G. (2000). Computer Networks and Systems. New York, NY: Springer New York. p. 72. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-1164-8. ISBN978-1-4612-7029-4.

- ^ Abate, J.; Whitt, W. (1987). "Transient behavior of the M/M/l queue: Starting at the origin" (PDF). Queueing Systems. 2: 41–65. doi:10.1007/BF01182933.

- ^ a b Harrison, Peter; Patel, Naresh M. (1992). Performance Modelling of Communication Networks and Computer Architectures . Addison–Wesley.

- ^ a b Guillemin, F.; Boyer, J. (2001). "Analysis of the M/M/1 Queue with Processor Sharing via Spectral Theory" (PDF). Queueing Systems. 39 (4): 377. doi:10.1023/A:1013913827667. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-11-29.

- ^ Abate, J.; Whitt, W. (1988). "Simple spectral representations for the M/M/1 queue" (PDF). Queueing Systems. 3 (4): 321. doi:10.1007/BF01157854.

- ^ Keilson, J.; Kooharian, A. (1960). "On Time Dependent Queuing Processes". The Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 31 (1): 104–112. doi:10.1214/aoms/1177705991. JSTOR 2237497.

- ^ Karlin, Samuel; McGregor, James (1958). "Many server queueing processes with Poisson input and exponential service times" (PDF). Pacific J. Math. 8 (1): 87–118. doi:10.2140/pjm.1958.8.87. MR 0097132.

- ^ Gross, Donald; Shortle, John F.; Thompson, James M.; Harris, Carl M. (2011-09-23). "2.12 Busy-Period Analysis". Fundamentals of Queueing Theory. Wiley. ISBN1118211642.

- ^ Adan, Ivo. "Course QUE: Queueing Theory, Fall 2003: The M/M/1 system" (PDF) . Retrieved 2012-08-06 .

- ^ Stewart, William J. (2009). Probability, Markov chains, queues, and simulation: the mathematical basis of performance modeling . Princeton University Press. p. 530. ISBN978-0-691-14062-9.

- ^ Asmussen, S. R. (2003). "Queueing Theory at the Markovian Level". Applied Probability and Queues. Stochastic Modelling and Applied Probability. Vol. 51. pp. 60–31. doi:10.1007/0-387-21525-5_3. ISBN978-0-387-00211-8.

- ^ Adan, I.; Resing, J. (1996). "Simple analysis of a fluid queue driven by an M/M/1 queue". Queueing Systems. 22 (1–2): 171–174. doi:10.1007/BF01159399.

- ^ Kleinrock, Leonard (1975). Queueing Systems: Theory, Volume 1 . Wiley. ISBN0471491101.

- ^ Harrison, P. G. (1993). "Response time distributions in queueing network models". Performance Evaluation of Computer and Communication Systems. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 729. pp. 147–164. doi:10.1007/BFb0013852. ISBN3-540-57297-X.

- ^ Stewart, William J. (2009). Probability, Markov chains, queues, and simulation: the mathematical basis of performance modeling . Princeton University Press. p. 409. ISBN978-0-691-14062-9.

- ^ a b c Coffman, E. G.; Muntz, R. R.; Trotter, H. (1970). "Waiting Time Distributions for Processor-Sharing Systems". Journal of the ACM. 17: 123–130. doi:10.1145/321556.321568.

- ^ Morrison, J. A. (1985). "Response-Time Distribution for a Processor-Sharing System". SIAM Journal on Applied Mathematics. 45 (1): 152–167. doi:10.1137/0145007. JSTOR 2101088.

- ^ Kingman, J. F. C.; Atiyah (October 1961). "The single server queue in heavy traffic". Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 57 (4): 902. doi:10.1017/S0305004100036094. JSTOR 2984229.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/M/M/1_queue

![p_{k}(t)=e^{{-(\lambda +\mu )t}}\left[\rho ^{{{\frac {k-i}{2}}}}I_{{k-i}}(at)+\rho ^{{{\frac {k-i-1}{2}}}}I_{{k+i+1}}(at)+(1-\rho )\rho ^{{k}}\sum _{{j=k+i+2}}^{{\infty }}\rho ^{{-j/2}}I_{j}(at)\right]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/199a5d293ed8310ee0f023ed8c5be0b139adfb7b)

![W^{\ast }(s|x)={\frac {(1-\rho )(1-\rho r^{2})e^{{-[\lambda (1-r)+s]x}}}{(1-\rho r^{2})-\rho (1-r)^{2}e^{{-(\mu /r-\lambda r)x}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/834c6b0b9f923076b830d4358853c1a60a080f7c)

0 Response to "M m 1 Processor Sharing Response Time Not Continuous"

Post a Comment